The author and the father

I shall bring you with me on a trip across the history of the Jekyll & Hyde myth. And I can't think a better place to start this tour than in a funeral.

Mount Vaea, Samoa. December of 1894. You are in a beautiful, quiet spot in the summit of the mount, overlooking the sea. A group of sixty native Samoans arrive, bearing on their shoulders the body of a dead man. The path they have used to get to Vaea's peak is new: the Samoans have spent the night cutting it. And during the night, while the young chopped and slashed trees, the old surrounded the corpse with a watch-guard of honor. That night, one of the elders made a speech:

We were in prison, and he cared for us. We were sick, and he made us well. We were hungry, and he fed us. The day was no longer than his kindness. You are great people and full of love. Yet who among you is so great as Tusitala? What is your love to his love?

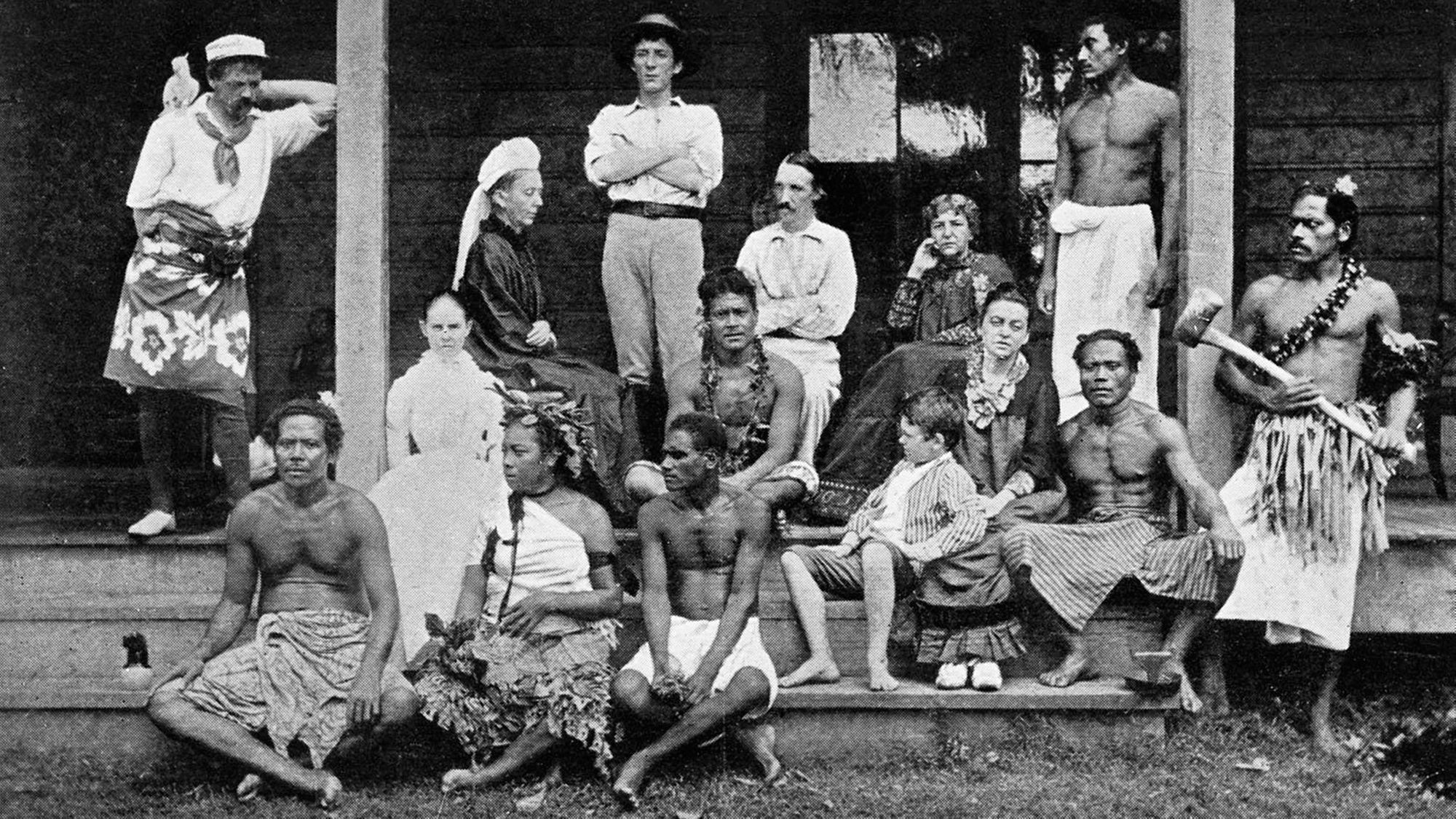

Tusitala. That was the name of the dead man. It means "Teller of Tales" in Samoan. Tusitala had died young, at only 44. Nevertheless, he had a longer life than most would have expected: since birth, Tusitala had been sickly and weak, incredibly thin, and being constantly tormented by hemorrhages.

Tusitala was loved by the Samoans, but he was not one of their own. Tusitala was a foreigner. His real name was well-known around the whole world, as the author or Treasure Island and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Tusitala was Robert Louis Stevenson.

Stevenson had made it to Samoa in 1890, 4 years before this scene, after an almost two year trip across the Pacific from San Francisco, on the yacht Casco. In the almost five years he spent in Samoa, Stevenson became the greatest defender of the natives, almost a saint. He publicly protested the behavior of the colonial powers in Samoa, even managing to get some officials recalled.

A legendary writer of boys' stories, the kind side of Victorian colonialism. A protector of the weak. This was Robert Louis Stevenson.

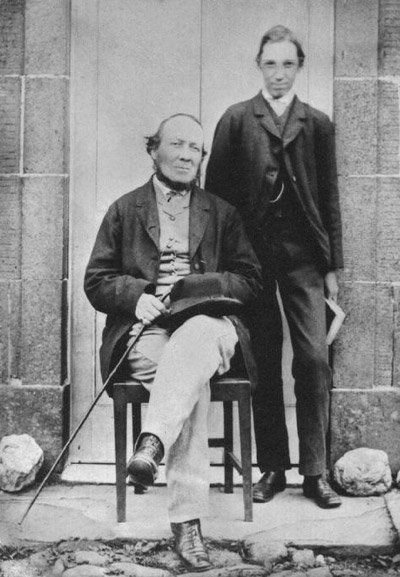

Edinburg, Scotland. January 30th, 1873. You are in the dining room of 17 Heriot Row, the residence of a bourgeois Scottish couple and their only son. The three of them are in the room. At your right, Thomas Stevenson, the pater familias. He is a pious, severe man. He is wealthy, having inherited the business of his father: his family has built most of the lighthouses that illuminate the Scottish coast. Thomas is a strict Calvinist whose faith has been rewarded by God with riches. Unfortunately, God was not so generous with his descendants. His only son, Robert Lewis, is a sickly young man uninterested in continuing the family business. He has very long hair, wears an extravagant velveteen jacket and his hat is so weird that provokes contemptuous laughter from the street urchins of Edinburgh. Unknown to Thomas, his heir has gone much further than wearing weird clothes: he is well-known in the brothels of Edinburgh; he uses the assignation that his father gives him to pay the prostitutes, and he is famous for having a liking on the older ones. His politics are very far from what good old Thomas would have considered acceptable: "a red-hot Socialist" he called himself.

Back in the dining room at 17 Heriot Row, you notice a very uncomfortable silence. There is a good reason: after years of doubt, Robert Lewis has just announced to their parents that he no longer believes in God (“am I to live my whole life as one falsehood?”). This young man has underestimated the effect that this declaration would have on his father. Thomas is barely able to reply, and when he does, he hurts his son deeply: “You have rendered my whole life a failure.”

Robert Lewis will regret this scene for a long time: "What a pleasant thing it is to have just damned the happiness of (probably) the only two people who care a damn about you in the world", he will write to a friend. This incident will shatter the Stevenson's family life.

Obviously, our present Robert Lewis will become Robert Louis: the creator of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Samoa's Tusitala. Nevertheless, he will never be able to shake off the guilt of this day. Stevenson's work is full of father figures, many of them accusatory: for example, in his final novel, Weir of Hermiston, has a judge condemning to death his own son, the protagonist of the novel.

Stevenson was always a rebel at heart, unable to answer the demands of his stringent, headstrong father; a father that, nevertheless loved him very much, and was loved back. He was probably never a monster, but he very much feared that his father considered him one. Anyway, this was Robert Louis Stevenson, too.

Bournemouth, England. Autumn of 1885. It's 9 years before Tusitala's funeral; 12 after the scene in the dining room of 17 Heriot Row. Robert Louis Stevenson is on the peak of his creativity. He recently married Fanny, an American divorcee ten years his senior (oh, poor Thomas!). Louis lives with her and with Lloyd, her son from her previous marriage. Against all odds, Fanny caused a great impression to Lewis family: he reconciled with them, to the point that old Thomas Stevenson has bought a house for them to live in.

One morning, during breakfast, the author claims to be "working with extraordinary success on a story that had come in a dream". He will write a first draft of 30.000 words in three days; following Fanny's advise, he will burn this draft, and rewrite the whole story again from a different point of view: the dream's story has to be an allegory. This story was Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

The plot of Strange Case Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is quite simple. Gabriel John Utterson, a lawyer, discovers by chance that a sinister-looking man, Mr. Hyde, is associated somehow to his friend and client Dr. Jekyll, a very reputable gentleman. Eventually, Hyde kills a person; he mysteriously disappears. For two months, Jekyll returns to his former sociable manners, but he slowly reverts back to refusing visitors. Finally, Utterson and Jekyll's butler hear a stranger's voice coming from Jekyll's laboratory; after forcing the laboratory's door, they find the body of Hyde, who committed suicide, apparently to avoid punishment. Through two letters, the truth is revealed: Jekyll and Hyde are the same person. Jekyll transformed to Hyde and back using a potion, but finally lost control, as subsequent batches of the serum stopped working. Realizing that he would eventually stay transformed as Hyde, he wrote a confession and killed himself.

That was the plot. Then... what's the point of it? It's obvious that the main theme of Jekyll & Hyde is the duality of man; Jekyll himself says so "that man is not truly one, but truly two". But what type of duality do these characters represent? Since its very successful release as a "penny dreadful" in 1886, dozens of readings have flourished. The Scottish Church celebrated it as a parable of the wages of sin; Victorians read it a moral tale on the horrors of the sexual appetite unleashed; elementary Freudianism see it as the battle in between the self (Jekyll) and the id (Hyde); nowadays, the most popular allegorical reading in Britain see it as a reflection on the divided identity of Scots in the United Kingdom. None of those interpretations are wrong. Moreover, all those readings are right in a way: that's something that only great allegories have.

Nevertheless, I do believe that some interpretations fit better the original text than others. Let's get back to the text. The following is taken from Jekyll's final confession:

the worst of my faults was a certain impatient gaiety of disposition [...] I found it hard to reconcile with my imperious desire to carry my head high [...] Hence it came about that I concealed my pleasures [...] I stood already committed to a profound duplicity of life. [...] Though so profound a double-dealer, I was in no sense a hypocrite; both sides of me were in dead earnest; I was no more myself when I laid aside restraint and plunged in shame, than when I laboured

This is the personal problem that Jekyll was trying to fix: he was tortured by the fact that he needed to conceal his pleasures. Jekyll (and therefore, Stevenson) never clarifies which pleasures were those that needed concealment, that was left to the imagination. Nevertheless, it's easy to see the connection in between Stevenson's reckless youth and the prude environment in which he was raised up, particularly his father. In this direction, one needs to add that Hyde's mischiefs are particularly targeted to faith and family:

Hence the apelike tricks that he would play me, scrawling in my own hand blasphemies on the pages of my books, burning the letters and destroying the portrait of my father.

On this line, the novella establishes that Jekyll's only faults may have been in the past:

He was wild when he was young; a long while ago to be sure; but in the law of God, there is no statute of limitations. Ay, it must be that; the ghost of some old sin, the cancer of some concealed disgrace: punishment coming, years after memory has forgotten and self-love condoned the fault.

Is Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde an attempt by Stevenson to exorcise his bad deeds when he was young? It's a possibility. Nevertheless, now the story had been given to the public, and the public would change its meaning forever.

How Mr. Hyde became Mr. Hyde

We started our trip with a funeral. It's only fair that we shall continue with murders. Five of them.

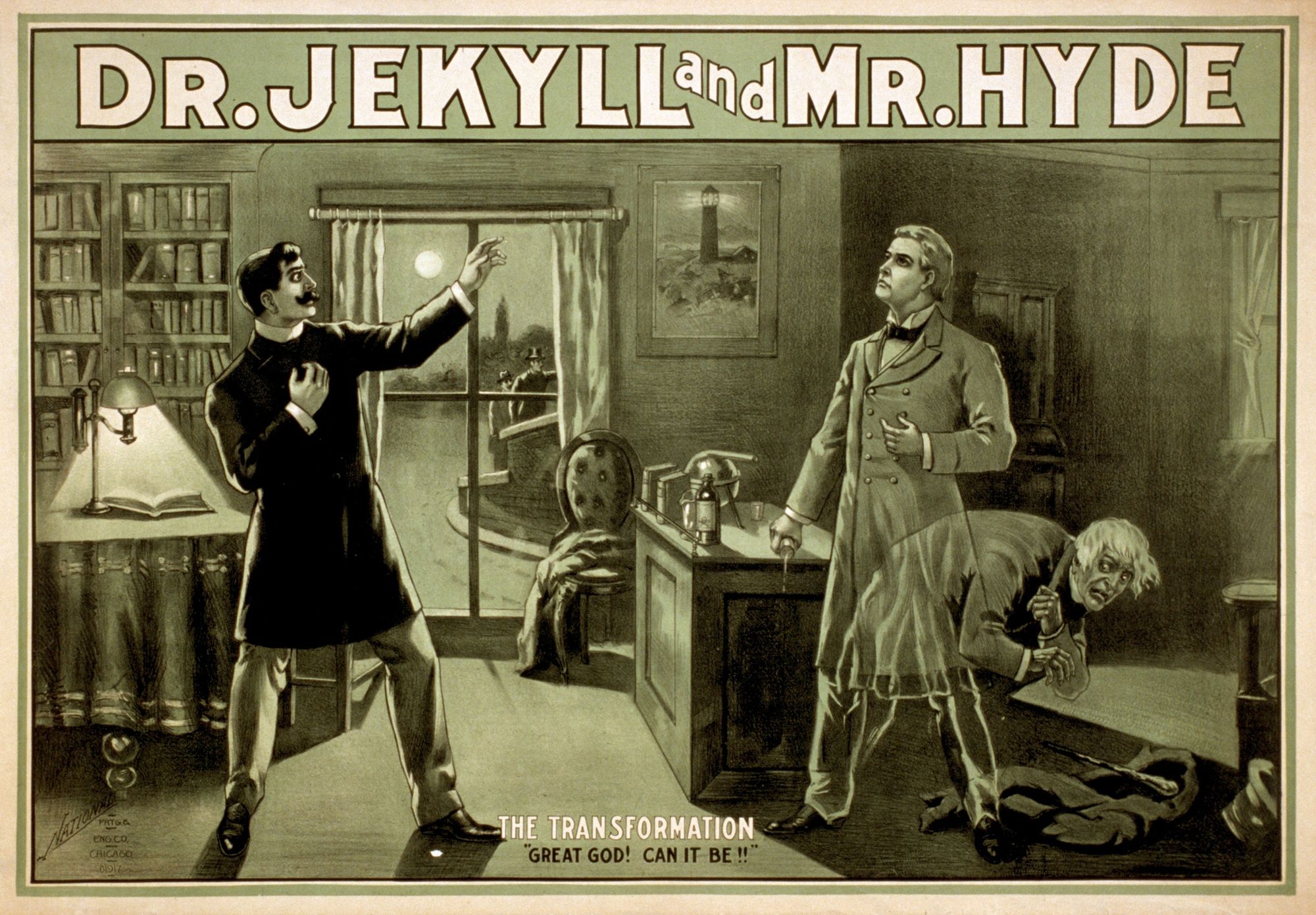

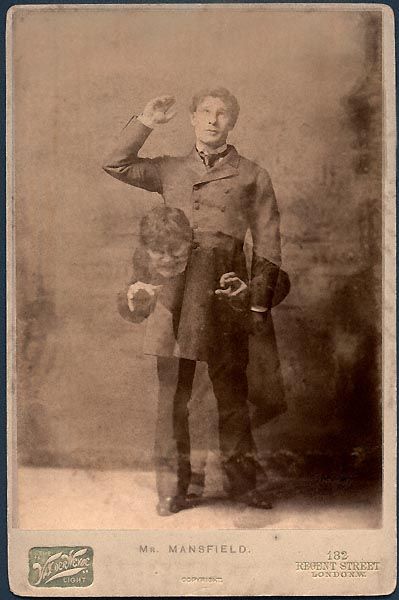

London, England. August 1888. Two events this month guarantee the immortality of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The first, the London premiere at the Lyceum Theatre of a play based on it in August 4, 1888. Richard Mansfield, a popular English stage actor, famous for his performances in Shakespeare plays, had taken an early interest on Stevenson's tale: the possibility of playing both Jekyll and Hyde fascinated him. He will co-write a stage adaptation that, while not brilliant, will introduce a very important element in the Jekyll mythos: women. There are no females of any importance in the original story; the play introduces a love interest for Dr. Jekyll. This element will later become more important in the long history of adaptations of Jekyll and Hyde. Unfortunately, the rest of the play innovations on the original story are far less successful: comic scenes catering to the taste of the times, and an unnecessarily big dramatis personae, big enough to supply work for a whole theater troupe, dilute the impact of the tale.

The other event of this month is far more memorable than the premiere of a mediocre adaptation to the stage, an event that would become forever intermingled with Jekyll and Hyde. On August 31, 1888 the body of a prostitute, Mary Ann Nichols, was discovered in the East London district of Whitechapel. She was the first of the "canonical five" victims of the legendary Jack the Ripper. Her throat had been severed by two cuts, and the lower part of the abdomen was partly ripped open. Soon, more murders follow, with similar gruesome mutilations. The nature of the wounds suggest that the author had a strong knowledge of surgery. A doctor, meaning a well-off man, venturing into the slums of London for committing crime: the public of London can't stop themselves of connecting the horrid murders to this new, morbid play. Many Victorians saw the connection with the apparently cordial Dr. Jekyll. Richard Mansfield, the author and protagonist of the play is accused of being the murderer: as one of the anonymous accusers claimed: "no man could disguise himself so well"! Fortunately, Mansfield was never arrested.

One of the many theories around Jack the Ripper is that the Dr. Jekyll and Mr., Hyde could have triggered his murderous actions. In any case, it's certainly an amazing temporal coincidence; anyway, we will never know. What we do know is that the gruesome murderer and the great duality tale will become forever linked for the Anglo-Saxon public. Many cinema adaptations, particularly after the 1960s, will have Hyde becoming a serial killer focused on murdering women.

Jekyll and Hyde, at the movies

We move forward in time. It's the 18th of March of 1920. Stevenson died 25 years ago, but his tale refuses to die. We are in New York City, and we are going to attend the premiere of an adaptation to the silver screen of Jekyll & Hyde, a film that will start a beautiful tradition.

The American film industry has produced three great adaptations of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The three share the novella's title. The first one was filmed in 1920 by John S. Robertson; the second one in 1931 by Rouben Mamoulian; the third one in 1941 by Victor Fleming. The three of them differ from the original tale, but, in a fascinating turn, they do it in an extremely similar way. Their digressions, based on the addition of a female interest in the theater version by Richard Mansfield, will pile up.

We could summarize that digression in between the American adaptations and the Stevenson's novella as follows: the origin of the Jekyll/Hyde division is sexual repression. In the three adaptations, Jekyll is engaged to a lady of high society (Martha Mansfield/Rose Hobart/Lana Turner). In the three of them, Jekyll is clearly haunted by lust: he wants to marry as soon as possible to fulfill his desires. In the three movies the father of the bride, slightly suspicious about the nature of Jekyll's studies, delays the wedding. Most importantly, in the three movies we found a new character that did not exist in the novella or in the play. This novelty is an attractive woman that captivates Dr. Jekyll, a temptress: an exotic dancer (Nita Naldi), a bar singer (Miriam Hopkins) or a waitress (Ingrid Bergman). This temptation pushes Jekyll into the creation of the transforming potion, allowing him to succumb to it through Mr. Hyde. Unfortunately, as time passes Mr. Hyde becomes both more powerful and more violent: he always ends up murdering the temptress, and eventually, committing suicide.

1920's version by John S. Robertson is the version that stablished this departure. It's also the least daring one. Nevertheless, it becomes a fascinating portrait of America's social fears in the early 20th century. In particular, anti-Catholicism; it sounds insane now, but the second Ku Klux Klan (1921-1925) targeted Catholic immigrants, that were depicted as non-white and therefore as a threat to the nation moral health. Good old Thomas, always worried that his son was spending too much time in Southern France surrounded by impious Catholics, may have understood.

In John S. Robertson version, the temptress that tantalizes Dr. Jekyll is a dark-skinned Italian. She is a dancer, performing something that it certainly looks exotic, but not very much Italian. The similarity in between how Southern Europeans were depicted in the 20s and how Latin Americans are depicted now, a century later, results obvious. And to make the whole issue even more revealing, the actress playing the role was not Italian, but from the other demeaned origin of Catholic immigrants during this era: Nita Naldi was Irish.

The greatest of this trio of masterpieces is the version created by Rouben Mamoulian in 1931. It's a movie that is only conceivable to have been done in the glowing Hollywood pre-code; it belongs to a rare breed of works, films in which American cinema was at the same time innocent and free. After industry moral lines created by Will H. Hays started to be enforced in 1934, Hollywood became prude; even nowadays, it's still the most self-conscious artistic industry in the world.

Nevertheless, we are now in 1931, and American cinema it's still a wild business. Mamoulian didn't plan to film Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde as a horror tale, with a villain and a moral to be learnt; in fact, he openly sympathized with Hyde. The following is extracted from an interview with him by Thomas R. Atkins for The Film Journal, recorded on November 28, 1972, at his home in Beverly Hills. I quote Mamoulian extensively, as I find his re-interpretation incredibly interesting:

In Stevenson's original work, which might be called a horror story, Dr. Jekyll is a florid man of 55 -a big plump guy who is irked by the restrictions of morality. I wouldn't even say Victorian morality- just morality. He'd like to indulge in all sorts of sexual excess and debauchery but can't do it as Dr. Jekyll, without losing face. His aim is to separate the two parts of his nature so he can have one hell of a good time and still keep up his hypocritical virtuous facade. I thought this interpretation was not interesting enough and not pertinent enough for the spectators who were going to see the film. I thought that a more interesting dilemma would be no that of good versus evil or moral versus immoral but that of the spiritual versus the animalistic which are present in all of us. That is our common dilemma.

Therefore, as a prototype for Hyde, I didn't take a monster but our common ancestor, the Neanderthal man. Mr. Hyde is a replica of the Neanderthal man. He is not a monster or animal of another species but primeval man -closest to the earth, the soil. When the first transformation takes place, Jekyll turns into Hyde who is the animal in him. Not the evil but the animal. Animals know no evil; they're completely innocent and much better morally than we are. Animals never kill except to eat. They don't torture each other. The first Hyde is this young animal released from the stifling manners and conventions of the Victorian period. He is like a kitten, a pup, full of vim and energy. He knows no evil, he simply gives vent to all his instincts.

One of my favorite scenes is when Hyde leaves the house and walks out in the rain. I had it raining very hard. The average Englishman would have opened an umbrella, but Hyde not only enjoys the rain, he takes his hat off and luxuriates in the rain falling on his face -like a young, innocent animal.

But, of course, he's not only an animal. He's partly a human being, and a human being -let's face it- is a very perverse creature. So because he is part human and possesses a human brain, which on one hand reaches heaven and on the other wallows in depravity, he begins to refine his unorthodox pleasures -cruelty, sadism, and murder. Gradually Hyde changes from an innocent animal into a vicious -I won't say beast because beasts are not vicious- human monster, a monster that is part of us but which we usually keep under control. Throughout the film you see Hyde getting worse, both physically and psychologically; and you also see Jekyll, instead of becoming liberated as he had hoped, deteriorating with Hyde. It's a sad story.

In Mamoulian's view, the point of the story was that Dr Jekyll "would like to indulge in all sort of sexual excess and debauchery". Hyde, his hidden self, was brought into existence to give him license to do so.

Nevertheless, this version is not great only because of Mamoulian's point of view, or even because its visual power. Despite the fact that the acting of Fredrich March on the double Jekyll/Hyde role made him worthy of an Academy Award in 1932, the modern viewer feels more persuaded by Miriam Hopkins, playing the illicit sexual interest that "awakens" Hyde. Hopkins was a Lubitsch actress who played the sensuousness of the role with delightful subtlety. The scene in which she playfully tries to seduce Jekyll in her room is a beautiful part of the history of cinema. Later in the movie, a fade-in of Hopkins' leg will be the symbol of Jekyll's repression.

And now, for the last of the trio. We are in 1941, with WW2 devastating Europe; the US is still not in the war (it will enter it in December, after Pearl Harbor). In a social environment in which very real monsters kill millions, MGM decides to remake Mamoulian's film: Victor Fleming will direct it. Despite the fact that the obvious similarities detract a bit from its viewing, Fleming adds a fantastic casting to the equation. Moreover, this version added the most memorable image ever inspired by Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. After taking the potion for the first time, Jekyll hallucinates himself riding a chariot, a chariot pulled not by horses, but by two women: his sweet fiancee Lana Turner and the tempting Ingrid Bergman. This is a clear -and very smart- references to Plato's chariot allegory, in which the human soul drives a chariot with two horses: one representing the rational or moral impulse, while the other represents the irrational passions and appetites.

As commented before, one of the peculiar beauties of this version is the cast: not only for it being all-star (Tracy, Bergman and Turner!) but for the cross-casting of Bergman and Turner. Initially, Bergman was supposed to play the virtuous fiancée of Jekyll and Turner the "bad girl" Ivy. However, Bergman, tired of playing saintly characters and fearing typecasting, pleaded with Victor Fleming that she and Turner switch roles. After a screen test, Fleming allowed Bergman to play a grittier role for the first time. It was certainly a great decision, as she is the most memorable of the trio.

And now, for the last stage of our trip. We will make a series of short stops across different interpretations of the myth during the last 50 years. After the sexual revolution that took place in most of the West during the 1960s, this interpretation of Jekyll & Hyde lost appeal: it did not make sense to depict sexual desire as the great evil other once sexual repression stopped becoming a major actor. Nevertheless, during the last 50 years two adaptations clearly stand out.

The first one is Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde. Produced by Hammer Film Studios in 1971, it was the third attempt by the venerable British company to adapt Stevenson's tale. Third time's a charm, they same, and it was certainly the case for Hammer: Sister Hyde keeps the spirit of the original, but brings it to a different place, a place of gender-bending and with the most murderous Hyde that we had seen until then. It would be easy to accuse Sister Hyde of misogyny, as the criminal persona of Jekyll happens to be a female, and one that happens to be as sexually active as Jekyll is prude. Nevertheless, it's clearly a much more complex film that it seems.

Dr. Jekyll et les femmes (1981) is the most distinctive take ever done on the original. This film, titled Dr. Jekyll and Miss Osbourne internationally, may very well be to Stevenson's fable what Zulawski's Possession is to Lovecraft's cosmic horror. It's a period piece, a slasher, a soft-core and an auteur film, all at the same time. Its direction in particular is incredibly idiosyncratic, even more taking into consideration that it's a horror movie; the movie won Best Direction at the Sitges Film Festival in 1981.

Beyond this two extraordinary films, there have been many others. Two of the most legendary names in Spanish horror cinema are also linked to the myth. León Klimovsky and his inevitable lycanthrope tried their hand in Dr. Jekyll and the Wolfman (1971). Jess Franco has been related to the myth through a rebranding his El secreto del Dr. Orloff (1964) was retitled The Mistresses of Dr. Jekyll.

In the 21st century the duality myth per excellence still inspires new adaptations across the world, particularly on TV. One of them is Jekyll, a very successful TV miniseries created by BBC in 2007, that adds a science-fiction spin to the classic tale and surprising parallelisms to the videogame Assassin's Creed, released the same year. A more recent one coming from Britain was created on 2015 by ITV, with the title Jekyll & Hyde. And the myth doesn't only attract admiration in old Europe: adaptations have also been done out of the Western world, inspiring a 20 episode K-Drama in 2015 (Hyde, Jekyll, Me).

A farewell

And with this, our little tour ends. What should we take out from the story of Jekyll & Hyde, and most importantly, of its development? J&H was written in a very open, abstract way; however, its readers, many of them living in Victorian Britain, gave it a sexual interpretation. Stevenson hated that; he once wrote: "people are so filled full of folly and inverted lust, that they can think of nothing but sexuality". Nevertheless, a piece of art always belongs to the public: J&H was a tale on the dangers of sexual repression because a big part the public decided so. And yet, others decided that this interpretation was wrong: Jekyll was a strict Lutheran facing the voluptuosity of Catholicism, or a good old Scottish gentleman fighting the English influence on the motherland or...

This, exactly this. I cannot think of a bigger praise for a work of art than allowing itself to an almost infinite number of interpretations. J&H survived the test of time because it is, as Fernando Pessoa would say, plural like the universe. Stories like this one are our archetypes, the basic pieces with which all the others are created of. Great works of art, like Shakespeare create humanity, transform society via changing its imaginary in an essential way. Jekyll & Hyde is one of these.